| COVER STORY | 08 23 05 |

Postcards from UsticaNearly two centuries ago, a young man named Dominic Verdichizzi left his homeland for New Orleans. This summer, Ronnie Virgets discovered what his ancestor left behind. By Ronnie Virgets |

|

| Many New Orleanians can trace their beginnings to Ustica, a flyspeck of an island off Sicily that once served as a debtor's prison and has been occupied by everyone big enough to build a navy. |

For many people in New Orleans, that place is Sicily. People with "Italian" surnames here are almost surely Sicilian. Check out a map of Sicily. Even the place names have resonance in our phone books: Caminita, Milazzo, Cefalou, Ragusa, Messina.

But even in this subculture, there is a subculture. Many New Orleanians can trace their beginnings to Ustica, a flyspeck of an island off Sicily that once served as a debtor's prison and has been occupied by everyone big enough to build a navy. I am one of these New Orleanians.

This summer, I came to Ustica. There are fewer pirates and more tourists than before, but it is still a place of loveliness and laughter. When there's such a small space between the top of the mountain and the bottom of the sea, it's a great privilege to be here.

All the cultivation, all the subjugation. But I will remain here, me or someone who looks like me. Someone close enough to be called family ...

The night before leaving for Sicily, a supper of General Tsao's chicken. In the requisite fortune cookie, above my six lucky numbers, the red-ink proclamation that "Your family is one of nature's masterpieces." We shall see, we shall see.

|

| We go for a tour-ride with Salvatore Verdichizzi, son of Felix and distant, distant relative. He walks like a duck, hence the nickname used to differentiate him from two other Salvatores: "Papero." |

Here we are on Ustica, a life-breathing 9-mile stretch of volcanic rock in the middle of the Mediterranean, and we are awkwardly smiling at each other: me, whose ancestor left long ago, and they, who have never left.

One of these Verdichizzis is Salvatore, a young man brown and sturdy. The other is an old lady who looks like Charles Laughton in drag, only a bubbly Charles Laughton. They peer at my face for some recognition, but already too much Hibernian, Alsatian, American has run there. But there's no sense of confrontation between the outlander and the Udiche, the son of traders happy to leave this outcropping of rock and the sea and the son of those happier still to stay in this place of beauty and laughter.

All I really know of the ancestor is that his name was Dominic Verdichizzi and that he came to New Orleans in the 1830s, far ahead of the large Sicilian immigrations. At some point and for some reason, the name was changed, and the family tree blossomed into a forest. Some of the blooms came to be called "Verdigets," "Virdagamo," "Verges" or even "Virgets."

Around 1936, Minor Dominic Virgets was introduced to Virginia Lillian Virgets. Two years later, they married, and years after that, I still have to explain my mother's maiden name. Once, I would have added -- to ward off the horrors of consanguinity -- "but they weren't cousins or anything."

I no longer add that.

|

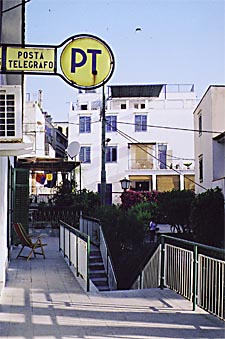

| Our house is adorable, and part of it is shared with the local post office. Shades of Eudora Welty. |

But what can probably never be known again are the reasons for that first leaving. A family quarrel? A young man's restlessness? A girl's angry father? Answers are well-hidden by time, but I'm on my way to look at the hiding place.

Already Christina has taught one Sicilian proverb: "If you have time, don't wait for time."

I have time to ponder meaning on the two-plus hours at chug-chug ferry pace between Palermo and Ustica. On the upper deck, an Italian girl of maybe 20, and she is surely the most beautiful girl I will see on this trip. A bit short in the leg, but fine and tan everywhere else. A lean heart-shaped face with a long jaw, Roman nose with the slightest imperfection, a rather small mouth with natural fullness and a slight sulk, and red-gold hair that the sea breeze keeps rearranging. A face artless and melancholy and kind.

A painting she is and perhaps the painting of an omen. Before I can think long on omens, Ustica heaves to.

The lived-in part of Ustica poses above a tiny port for a picture postcard. But you don't have to look far for nothingness. The remoteness that sometimes deluges what's left of my soul surely had its origins here, this nine miles of island rising steeply from the bottle-clear waters of the Mediterranean. There is something magical in places where shifts in tectonic plates stand just next to the jealous, reclaiming sea and flash unique and startling birth scars. It is a place where gods are born.

|

| Sicilians love to be outdoors; it is warm, so why not? The bent and bending men are best at it, spewing the rarely sighted but prevailing Male Gossip. Knowing talk, yes, all-knowing and bawdy, too. We -- our lives -- bump into, collide with, melt into one subculture after another. But some touch something in our secret home. The place where we started. |

Our house is adorable, and part of it is shared with the local post office. Shades of Eudora Welty.

Our hostess is Christina, 24. She speaks English and is cousin to travel-pal Laura Gucchione, who spends most of her time in Bywater. Because of her, we have a guide, translator and public relations adviser.

The church bell at San Bartolomeo rings all night, but it has a light, happy sound, not one of those for-whom-the-bell-tolls sounds, and steals not a second of sleep.

A midnight ride around the rock, till there is a visual convergence of sea and lighthouse and moon full to bursting, all atop one another, all shining and shimmering in turn. The proper signal from destiny.

The meal begins with antipasto, then pasta, then meat or seafood. Then salad, then fruit, especially pears as big as grapes and figs as big as softballs. Also tiny wild strawberries that taste the way strawberries should.

And other things good to eat. A dark chocolate named Jacio that resembles a black nipple and olive oil that's too good to get sold to exporters. People around here should weigh 200 kilos each. All the walking must keep it down.

|

| A place of shutter and tile, flat roofs of hillside unevenness, muraled walls and surprising vegetation. |

And the walking keeps down the driving. Why allow Sicilians cars? They can't drive and don't care. The gnashing of tires, whirring of underpowered and overused engines, honking of impatient horns. Driving is like speaking; it is done for the noise value first and foremost. Yet the language is beautiful, and people sing, not speak, it. The driving is not beautiful.

People seem to have learned to anticipate the follies -- the stops, ease-overs, cut-offs -- of every other fool on the street. Even the unexpected and lengthy use of reverse; why pay for a gear and not use it?

Sicilians know one another at a glance. Else there would be a crash every corner and a fatality every other one. So maybe there is something beautiful about the driving.

Swam in the sea today at Spalmatore, in chilled Aquavit. Cut my wrist on the rocks and loved it anyway.

In the afternoon, hiked alone to the Ustica cemetery, which is on a hillside next to the sea. Death, your stinger just gets duller here. Counted the tombs of five Verdichizzi relatives: Vincenzo, Antonia, Rosa, Giuseppe and Felice. All during the day, I paid attention to Ustican children at play, so I saw the Verdichizzi clan all over again.

|

| I walk into the rectory of San Bartolomeo, past plenty of photos of St. Joseph's altars past, to look up the baptismal record of Dominic. It's there, inked neatly in the ledger for 1812. |

In late evening, Christina's friend Vito took us to an old jail built in Bourbon times, now restored. Nearby is a modern sculptural devotion to the jailed everywhere. Titled "La Boca del Lupo" (Mouth of the Wolf), it features a gate with hanging shackles and iron walls on each side. Only straight overhead is the "free" sky because that was the only thing seen by those locked inside.

The more you learn of Ustican history, the more you hear of smugglers and turnkeys. Odd how what was once a land of cast-offs and punishment now lures the leisurely with the promise of pleasure. And the tales of terror no longer scare, but the tales of pleasure more easily titillate. The imagination no longer wants to work on horror.

Does any of this sound familiar?

Their mosquitoes can't beat our mosquitoes. All buzz, no bite.

Sicilians love to be outdoors; it is warm, so why not? The bent and bending men are best at it, spewing the rarely sighted but prevailing Male Gossip. Knowing talk, yes, all-knowing and bawdy, too; you can see that, even without understanding a word. If Italian is sung, not spoken, this sounds like a dirty song.

|

| In the afternoon, hiked alone to the Ustica cemetery, which is on a hillside next to the sea. Death, your stinger just gets duller here. Counted the tombs of five Verdichizzi relatives: Vincenzo, Antonia, Rosa, Giuseppe and Felice. |

In front of the church is the town square, and on into the night are the old men and people of all ages and dress. Grown-ups sit at tables and talk excitedly, and teens lounge on the church steps and talk conspiratorially, and their little brothers and sisters run around the square and talk delightedly. Sicilians haven't lost the knack of coming together as a community and drawing entertainment and comfort from that.

The equivalent of the old New Orleans "lost bread" is called "panne caliato." Day-old bread soaked in water, add oil, vinegar, oregano, salt. Sometimes put in a bowl of milk or cream ...

There is something so transparently reasonable about shutting down commerce between the hours of 1 p.m. and 4 p.m. in the afternoon. The "Respiteo." Any business within a certain range of the equator should be mandated to do the same.

Birds, even the white-bodied blackbirds, sing loudly here. How did they come to be here? From what land did they fly and why? The ornithologist would have what he calls an answer, but we would more correctly call it a guess. Anyhow, it makes for a sea-sweetened song.

Unusually, there is no soccer field on the island of Ustica. There is, however, just astride of the perfectly blue sea, a well-tended baseball stadium. These are clearly a people who go their own way.

|

It takes only a small reflection to touch the possible forays of fate here. What clumsy conspiracies were hatched by a persistent fate to move this young man from Punticedda to Poydras Street? How and why?

Some found books only lead to evidence of lost libraries.

The air is "iodio." Christina believes it is better here. All her allergies are blown away, and she has more "energy."

The boat is borne along in such air, the boat skippered by an old replica of Trevor Howard, to some of the caves, or grottoes, along the shoreline. Breathtaking, and you'll likely never again peer so completely into the heart of water. One of the caves is named "Azzura" (Blue) and one "Verdi" (Green) because those are the colors of the water in the caves. Lapping against the gnarled rocks, vomited up by a queasy volcano how many eons ago?

|

More rowing. Winging around the Cave of Secrets are ... pigeons! Those winged-rat scourges of urban green spaces everywhere. And here comes the Coast Guard boat, which is apparently ticketing some scuba divers for breaking the rules.

Pigeons and regulators. What nature does not supply to discolor a pristine paradise, men are more than willing to supplement.

In Sicily, everyone rates a statue. There's one for Vito Longo, once mayor of Ustica. Already I've seen ones for William II, Verdi, Garibaldi, Hercules and the Four Seasons. Plus every saint God has heard of and a few He hasn't.

Went out to eat at a pizzeria (less taste and grease than ours), and on the way home, saw a house half up a hill with the front door and windows thrown open, revealing fine mirrors and well-lit furnishings. Christina says townspeople say that is exactly the point of all this revealing.

In the carnezzeria, picked up yesterday's newspaper and on several pages couldn't even begin to guess what was happening. Besides a renewed understanding of the Tower of Babel story, it was a good reminder of how easy it would be to break loose of the 24-hour news cycle addiction, especially the TV part. It's been a week without any "news" about Michael Jackson, the Saints, the Runaway Bride or Nancy Pelosi, and yet all seems right with the world.

It's hot, but if you move without enough hurry you get by. Even without air conditioners or even fans ("You'll catch an evil wind and die.").

I sit in the shade of the courtyard and smell that Christina and Laura are cooking something with fennel. Laura was here when she was a baby, but that was more than 30 years ago. Yet whenever she meets a family member, they have a snapshot or a story. The intra-family solidarity that is almost a cliche since the Puzo-Coppola pairing is here and it's still real. What takes its place? Religion is fading faster than family. Government? The final triumph of bureaucracy is superior to what it's replacing?

In the hallway, Christina's grandmother hung a painting 3-feet-high of baby Jesus in the arms of St. Joseph, father and child. It's not a religious picture so much as a real family picture.

We go for a tour-ride with Salvatore Verdichizzi, son of Felix and distant, distant relative. He walks like a duck, hence the nickname used to differentiate him from two other Salvatores: "Papero." He walks like my son Mike, is single and likes women, and is a baseball catcher and a kidder. He is a faraway son, and he is mine for a day.

He takes us on a tire-ripping trip to an old French fort that tops the island; amazing how placid and well-planned everything seems at that height. A falcon brings down a black bird larger than itself. The man still named Verdichizzi keeps a close eye, especially on the high and rocky places, on the guy who's given up that name.

We finish up with a feast at the Hotel Clelia, featuring large delicately fried shrimp and spicy pygmy shrimp and tales from Vito about the imprisonment of Libyans here in the 1920s. After enough grappa and Leone white wine, it is time to toast the Duck: "An old man may not have a clear idea about where he is going next, but he can find out where he has been. Thank you for helping me do this."

Farewell, Ustica, where there is lavender and yellow-winged sparrows and crazy old men and noisy scooters and a fish cart and children of all ages.

As the ferry backs away from town, the 5 o'clock sun cascades on the blue sea and looks like 10,000 silver butterflies hovering on the water's surface.

Other Stories by Ronnie Virgets:

Ronnie Virgets Archives